Why do less expensive galleries deal better with art criticism?

The case for a postcode-based provision of press in London

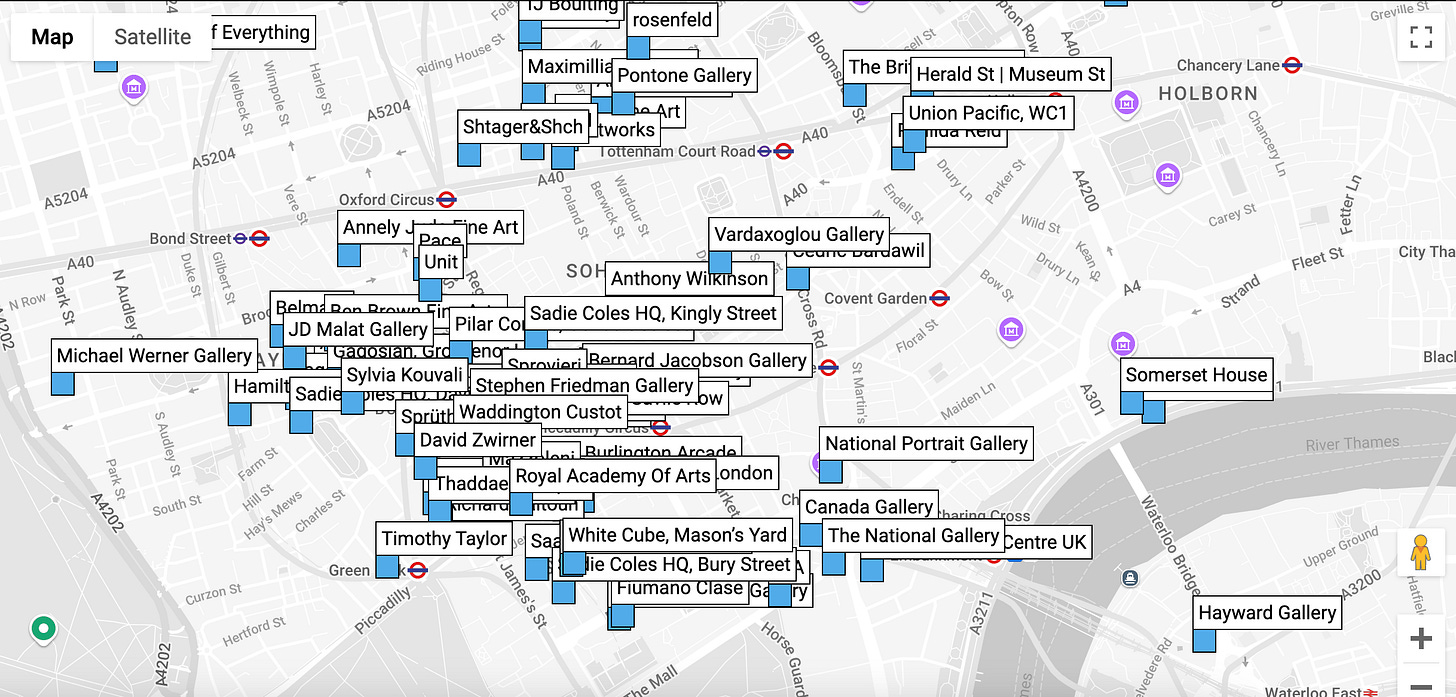

It’s an old adage that you can tell what sort of art a gallery is selling depending on the first letters of their postcode.

Starting in Central, the line between “crooked money for good art” and “good money for crooked art” runs roughly parallel to Tottenham Court Road, somewhere between David Zwirner and Alison Jacques with a slight detour to include Pilar Corrias in the former camp and Frith Street Gallery in the latter. Naturally, prices tend to go up the further West you go: more intricate lines can be drawn along Soho Square and Wardour Street, but by the time you hit Savile Row you’re firmly in Big Money territory and can generally start adding a zero for every block south of Maddox Street. This is the sort of art you can expect from any Western metropolitan city center; a bit of good, a bit of bad, a lot of expensive, mostly oil and acrylic paintings with the odd sculpture thrown in to retain a ‘multimedia’ status, usually made by artists who firmly believe they’re going to change the world.

Once you get south of the river it gets looser: performance and installation art reigns supreme in the SE1 area and how a lot of the more popular galleries make any money at all is a mystery even to me. Everybody involved is usually young, beautiful, pierced and tattooed, too proud to take government grants and too sui generis to accept loans from the bank of mum and dad. I have never been handed a price list further than Bermondsey. Naturally, it’s all meticulously curated and chockfull of artspeak press releases that eventually ends up making sense — my assumption is that areas like Peckham and Brixton have avoided the post-Covid curse because the majority of their buyers are local and therefore unaffected by the post-Brexit fees that have claimed so many victims this year.

An increasing desire to champion minorities (or to appear to do so) also plays a part, and I don’t only mean in terms of artist identity. Any gallery with a curation ready to claim a challenge to the white cube ethos will benefit from a huge wave of media attention (evidence by the countless emails in my inbox trying to follow the ginny on frederick formula, who exploded onto the scene last year as a ‘revolutionary confrontation of the traditional gallery structure’ — before promptly becoming one of the best-received booths at Frieze). This is most evident in East London, and in all fairness there are some great E1 galleries making genuinely impressive strides towards breaking out of the long shadow of what Sewell called the Serota Tendency; the support and propagation of art that might realistically be chosen for the Tate or Turner Prize. These are also the galleries where the best drugs will be offered — as a cause or consequence is anybody’s guess.

Heading South, SE8 generally guarantees a good blend of well-priced and well-made art; this is partly because many of the newer galleries in the Deptford area have made the very wise decision to hire a blend of art and finance people. An example of this is Elizabeth Xi Bauer, whose consistently impressive program is headed by Maria do Carmo M.P. de Pontes, but whose overall team is made up of a fair number of people with purely financial backgrounds. The result is a very clean (and economically viable) tenor that fits the bill both intellectually and fiscally, and to nobody’s surprise means the art is not only good in and of itself but cannot be dismissed as a financial fluke.

That being said, getting this balance wrong results in the sort of institutions found dotted around the Royal Exchange and City, galleries I affectionately refer to as red-chip refuges. These are marketplaces designed to appeal to people with a fair bit of money but little to no knowledge of art. I have my doubts that hyper-realistic ballpoint portraits of pitbulls wearing Gucci jackets or smashed Ruinart bottles encased in perspex resin really do increase in value (they certainly haven’t since 2015), but they do look good in a first-year-at-PwC’s apartment in Canary Wharf. Most importantly, they imply the owner’s vested interested in art without the need for any grasp of art history (or a development of taste beyond what was being shown in the lobby of whichever ghastly hotel in Dubai they stayed in last summer).

I promised myself (and my publicist) that I would avoid naming particular galleries but I would be amiss to mention the London Art Exchange’s clip of their head curator very confidently referring to Renoir as an Old Master before going on to mispronounce his grandsons name and say that palette knives “sort of come in and out of style”. It’s a genuinely endearing piece of media that, despite being in W1, captures a significant portion of the EC3 ethos. I don’t discount these sorts of galleries entirely because they do throw good openings (and generally have real champagne instead of prosecco) but there’s only so much meta-irony one can squeeze out of an anti-capitalist Banksy hung across the street from a Louis Vuitton.

I receive, on average, five emails a day asking me to write about every single type of these London shows. If they manage to get my name right (“Dear Victor Cumshot-Kershaw, hope this email finds you well…”), one of the first things I look at is the postcode. This is partly to figure out how easily I can fit it into the ol’ Thursday evening gallery-hopping schedule (nothing worse than RSVP’ing to two events so far apart that the booze from the first has worn off by the time you reach the second), but it’s mainly due to fact that the location of gallery will not only reveal what kind of art is being shown but what sort of article is being expected.

Before the accusations of snobbery start flying I will I will say that I generally don’t even bother visiting galleries in the Mayfair area, yet alone provide press. W1J and W1K galleries tend to sit at the very pinnacle of terrible art sold for revolting prices. They’ll invite you to an opening, ignore your repeated requests for a press release/price list while you wrestle over warm white wine with a gaggle of coked-up Love Island publicists, then hound you with emails asking where the coverage is (extra points if they throw GDPRs out the window and openly cc all the other poor sods who fell for the bunco). And the art sucks.

(I discount JPR Media from this rant, who have consistently introduced me to very good artists).

This also goes for any W1 gallery south of Old Compton Street (I tend to count The Smallest Gallery in Soho, which last I saw was showing some really great sculptural works by MEI MEI, as a cut-off point). Anything further tend to be goliaths that are about as interested in what you have to say about their awful art as they are in making the art less awful; which is to say very little. This is understandable to an extent - there is nothing I or anybody else could say about On Kawara’s cult of personality that hasn’t already been said, or indeed that would dissuade potential buyers from participating in it, so why pay some poor PR intern to deal with a contrarian alcoholic rehashing Joseph Kosuth?

They want fluff-pieces. In fact, I would generously say that the upper two-thirds of London galleries want fluff-peices. Sean Tatol pointed out years ago that the vast majority of art criticism today is PR and, for all his faults, he continues to be proved correct. We are paid to describe not to discuss art. If I wrote what I truly thought about the Koons and Kusamas I’m usually asked to big up I simply wouldn’t get paid. I’ve been commissioned by major papers to write about major galleries, only to have the offer revoked after the first draft was sent in: “your tone is perhaps a little too sharp for this particular show”, I am told. Interestingly, my tone has never been a problem when I’m singing a gallery’s praises. Simply put: they’ll pay me if I bullshit.

This has never been the case for galleries that sell their works for under £5,000. That is the cutoff point. I couldn’t tell you why this is the magical number that makes gallerists and press officers suddenly so much more open to critical discussion and repositioning of their artists’ works and/or curation. In this framework, I’ve had my critical works quoted in following exhibition texts. I’ve been asked to draft entirely new exhibition texts for artists I’ve panned. I’ve been personally sent very gracious rebukes to very ungenerous claims and have been invited to watch as I am proved wrong (I’m usually not, but it’s the thought that counts). But one thing remains constant: all of these acts have come from galleries selling their works on the lower end of the market.

It’s too easy to say that this is because these galleries care more about the art than the money. There must be other factors: perhaps the idea that any press is good press is more appealing to galleries run by younger, more grounded owners. Perhaps it’s that galleries who are charging less are simply more confident in their work, and therefore readier to defend their artists because they don’t have a hefty price tag to fall back on. It might also be a case of bandwidth: the smaller a gallery, the more time they have to parse through what little is written about them, and this translates into a more vested interest of critical opinions.

It would also be easy to say that none of this matters and I’m participating in a exercise of pure self-indulgence, that what I or other critics have to say is entirely irrelevant and useless (does it count as insider trading if I’m trying to convince the hot Italian at Gagosian to hire me to write about their Davies Street exhibitions again?). This may very well be the case, but looking at how reactionary media affects its progenitor is always interesting: even from across the pond, seeing how both subject and creator of the Scorned By Muses series have spuriously reconstructed their respective digital domains shows that there is still plenty of (if not more) space for referential works to affect both subject and audience's presentation of themselves. It’s the same reason US-based Spite comes up so often at literary events in London; any framework that alludes to itself by default will become a part of the scene it comments on, regardless of whether this is born of sardonic parody or scrutineered concern.

Like Sewell, I’m under no illusion that a snarky article about Maria Balshaw will change how the Tate functions. I do, however, believe that the more authentic and the closer to the ground an institution or gallery is, the more they will see the value in commentary and criticism of the work it puts forward. The most memed email my magazine ever received targeted one my favourite writers, who had gently probed the ethos of an affordable event that featured very affordable but very bad artworks. I think the fact that I am concerned to mention their name says enough.

I repeatedly have to tell my younger writers to expel empty phrases like “subverts expectations” or “invites the viewer in” from their vocabularies. I also have to tell them to be bitchier, constantly, especially in regards to big institutions. Nobody at The National Gallery will lose sleep if you say the exhibition text for The Hay Wain is a bit shit, I remind them. I understand the apprehension, of course: being anything other than hugely positive about everything forever all the time will result in backlash. Sophie Nowakowska bravely pointed out that Saatchi Yates’ Reflections was a bit of a hack job and was immediately called a racist. I haven’t seen Tabish Kahn say a single critical thing in all the years I’ve followed him— but then again, he is one getting invited to things. Tatol is not.

There’s a reason that most art critics are anonymous. From DivaCorp to bitter_reviews to spittle, art writers who dare be anything other than complimentary find themselves in a position where namelessness is the preferred option. This isn’t due to some bizarre, arbitrary desire to be liked, but because it’s the only way to actually get to the nitty gritty without hobbling yourself. The only pitches I get sent to my magazine are ones designed to sing the praises of an artist or institution — sometimes good, sometimes not, at which point the editorial process becomes nothing more than an exercise in personal taste. Hell on earth. People are well aware that there is nothing more suicidal than having their name associated with anything ‘mean’.

Attaching your name to genuine critical thought results in an odd in between state where you can’t fully express yourself but also can’t get paid. I am in deep and quiet awe of those who chose the latter path; I am too rapacious and attention-seeking to put my genuine thoughts above an extra couple hundred quid to spend at the pub. I assume there is also a certain element of glamour to the whole thing: DivaCorp got a ruminatory shoutout in On The Rag, one of the highest honours any current cultural commentator can aspire to, and I always feel a bit smug when somebody asks who runs spittle and I get to pretend I have no idea. I get it, truly: up until two years ago I would introduce myself as “Penelope Kensington” when traveling overseas on the off-chance that an artist would know that I was a critic and adapt their behaviour (I stopped after a Zwirner rep recognised and consequently berated me at Basel). This fear is so common in that it’s actually a major plot point of The White Pube’s novel Poor Artists, which against all odds (the ICA sells it) was a thoroughly enjoyable read.

As I say, I have huge respect for those who purposefully function both outside of this framework, and I do think it goes beyond the purely social: whatever their motivations, there are the people quietly holding together what’s left of real criticism and artists responding gregariously to it.

In the meantime, my heartfelt thanks to the galleries who not only expect but embrace it. I’ll let you in on an industry secret: be hot, have good booze at your shows, and get your fucking names right.