Experimenting with Sewell

"Communists, fascists and low church Christians": who benefits from the palingenesis of late art critic Brian Sewell?

There are few terms in art journalism that make me want to quit my job more than “provoking discussion”. Anything that claims to “generate discourse” or “foster dialogue” is a self-admission of an inability to communicate its own message: if your audience has to do the thinking for you then I’m afraid you’ve already lost. In the immortal words of Brian Sewell, it is the last resort of those who “haven't the foggiest notion of what their work may mean, but take the chance that to someone, somewhere, it may mean something".

Sewell, of course, has been on my mind lately. The Evening Standard has revived the late critic via a one-off, AI-written review of new Van Gogh exhibition at the National Gallery in order to, you guessed it, “provoke discussion” about artificial intelligence and journalism. This is a great shame for a number of reasons: real art writers need jobs (coffee and cigarettes aren’t cheap, you know), Sewell’s brand of cynical classicism isn’t particularly useful or relevant to modern audiences (you can find even his most controversial of opinions echoed today by the dilletantes in Justin Bua‘s comment section), and there is very little left to be said about Van Gogh or the National Gallery in the first place (unless someone wants to write a hit piece on the ugly-hot bartender at Ochre who keeps serving me watered-down martinis). Sewell may have been a contrarian in his time but his works now read more like a caricature of an art critic than anything else; salaciously uncomplimentary, spiteful commentary that duly positions the author as panjandrum-par-excellent (which he was in a way, but more on that later). The real shame, however, is neither economic or creative, but intellectual: we must ask ourselves what we believe to gain by indulging in the sort of dualist-determinist philosophy that equates the ability of the common language model with that of the human mind.

One of the great joys of indulging in any art critic’s cult of intellectual personality is their ability to surprise. The personal and psychological palate of an individual (regardless of institutional or academic fealty) is a fundamentally unknowable and therefore interesting factor. Sewell certainly made a name for himself by being, as Charlotte Scott put it, “a dick”, but he was a dick with taste informed by years of, well, being alive: writing, researching, traveling, copulating (quite a lot, according to an article he wrote in 2011, although the same article’s claim of being Philip Heseltine/Peter Warlock’s son is much doubted).

It should seem obvious that the collation and analysis of every single one of the experiences that might and did affect his judgement and perception of art and her institutions is an impossible task. AI does not have a childhood wallpaper or a ex-lover’s perfume (I immediately dislike any show where I catch a whiff of Chanel Bleu). We may some day develop an AI model capable of anatomising every synaptic snap to recreate a mirror of a personality, but both a 1930s psychoanalyst and a 2020s grief-tech mogul will tell you that this reality is still far off. Before the publication of the London Standard’s article, I fed GPT4 a selection of Sewell’s 2012 collection Naked Emperors: Criticisms of English Contemporary Art and asked it to behave as its author. I then asked the model (whom I eventually nicknamed BrAIn) a few basic questions about itself and its opinions.

BrAIn correctly sussed out that Sewell was a hater at heart. With hilariously little prompting, it told me that Michael Craig-Martin was a “charlatan and a dullard” who, if he had not been a Trustee of the Tate, would rightly have had his “excretable” work “flushed into the Thames”. As for the Tate itself, BrAIn dubbed it an “institution of fools, vast pomposities, intellectually null and aesthetically void.” It called Hirst a “prankster”, Freud the most “abysmal draughtsman to ever be mistakenly celebrated as a great painter” (a direct rephrasing of his 2010 article on the Pompidou’s L’Atelier) and Gilbert & George “disparing scatophiles” (an excellent heavy metal band name). I even asked it what it thought of Banksy; although it didn’t go quite as far as saying that he should have been put down at birth (to this day, still one of the funniest things a critic has said about an artist), it did call him a “half-baked pseudo-anarchist whose wit could barely fill a thimble”.

So far, so good. The cadence and vocabulary is certainly there, although there lacks a certain upper-class Britishness to the whole affair: phrases like “asshole’s anti-art” really highlight just how much of the literature GPT is trained on is published by and/or for an American audience. The tell-tale humdrum syntactical structure that plagues this iteration of the model is also present (notably the repetitive use of SVO, transitional phrases and parallelisms) but I’m willing to overlook this is favour of simply delightful phrases like “all the use and aesthetic allure of a rusted syringe”.

Most importantly, however, the model showed itself capable of predicting at least some of Sewell’s taste. I asked it to form its judgements solely from the information that could be parsed from the selection of essays I gave it, which in turn were focused mainly on museo-institutional reviews and group exhibitions rather than retrospectives or artist-led shows. GPT4 is prone to ignore these kinds of instructions and go searching for information online, but I do think I convinced it to limit itself to what I had given it. He famously disliked Banksy and Freud but the model did correctly assume his lesser-known disdain for artists like Bacon and Hackney as well as his begrudging admiration for Gormley. I was particularly surprised by the last one, as it eliminated the chance that the model assumed an automatic position of contempt for all contemporary artists.

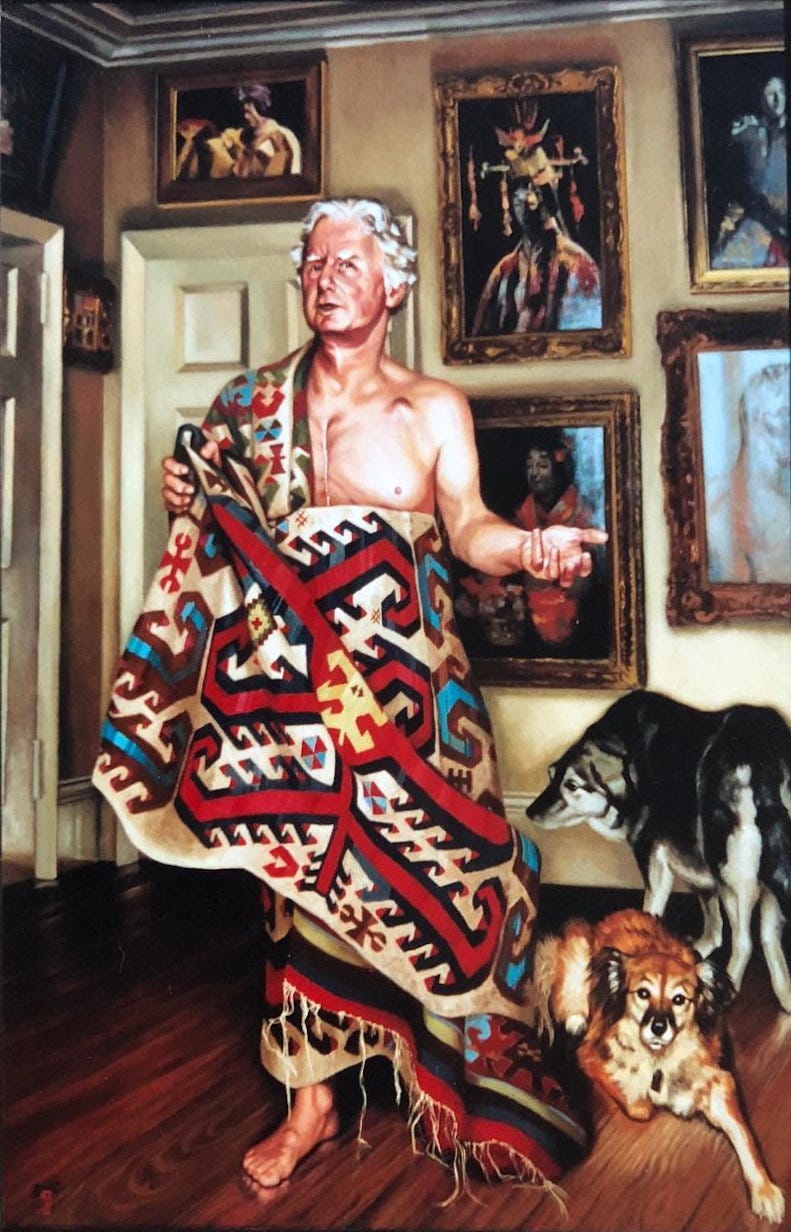

The surprise was short-lived, however. My inkling that the model would be unable to predict Sewell’s true taste was proved satisfyingly correct when I asked it a very simple question: “what do you think of Richard Harrisons’ art?”

The answer came as follows: “Harrison’s work is an empty exercise in formalism. He has has mastered the art of evasion capable only of hacking out the empty mannerisms fully developed a quarter of a century ago.” This would be a believably par-for-the-course answer if not for one tiny fact: Sewell adored Harrison’s work. His 2010 book Nothing Wasted is dedicated wholly to singing the man’s praises. Without access to this pre-established opinion, BrAIn had failed to understand whatever element of Sewell’s psyche allowed him to fawn over the sort of art that even his contemporaries expressed surprise at his affection for.

I was willing to admit that my experiment had flaws and my findings were, at best, pessimistically unreliable. Surely, I thought, the Evening Standard will have a much, much more comprehensive set of data to work from. Not only will they have access to every single one of Sewell’s published reviews, they will likely be able to train their AI on unpublished works, personal correspondence, and audio recordings and interviews tucked away in their own archives as well as those of Christie’s/Paul Mellon. They were also probably working with a slightly more sophisticated or at least personalised language model than GPT-4 and their editors will be competent enough to alter the uniform predictability of the model’s syntax.

I was wrong, of course. The article is a fucking mess. I’ll link it here if you’re interested in reading it, but it’s exactly what you’re thinking: a charmlessly catty caricature of a charmingly catty man. It’s also clear that from a history of art perspective the editors have no idea what they’re talking about: the article’s main angle of attack is the “emotional mawkishness” that runs as a thorough line throughout the show, titled Van Gogh: Poets and Lovers. Sewell probably wouldn’t have loved this kind of earnest naming convention but he would have been well aware of the post-war efforts by French and British dealers to reposition Gogh’s work as an extension of the post-impressionist "sensitivity” in order to appeal to aristocratic Americans. Sewell would not have dismissed this curatorial choice as an exercise in psychology, but as a deeply boring throwback to an already well-trodden reading of Van Gogh’s cult of personality. Or maybe he would have fallen in unrequited love with the coat-check lady and felt that the myth of the tortured artist framework was totally appropriate. My point remains: who fucking knows, and what does anybody gain by pretending otherwise?

Sewell attributed this kind of work to “communists, fascists and low church Christians”: objects d’art reborn through conceptual reconstruction. The white cube of the 60s and 70s turned the dropped glove into a thaumaturgical object to be venerated as in a church; excursuses like that of the Evening Standard’s pull this framework of intellectual posterity into the digital age. The job of conceptualising, it says, is no longer yours: not as artist, not as audience, and now not even as auditor. The only people who benefit from this are, as Sewell predicted all the way back in 2006, those “patently undemocratic” forces that slither back and forth between the artistic establishment and those too stupid to challenge her: “answerable to nobody, judge, jury and propagandist for itself, stubbornly reliant on a very narrow-minded group of dominant advisers, unrepresentative of anything other than the Serota Tendency.” RIP, king.